HIV's hidden reservoir

Interview with

HIV affects thousands of people, and treatment is very expensive. John Frater  from Oxford may have found a way to spot patients who could periodically stop their treatment without any ill effect.

from Oxford may have found a way to spot patients who could periodically stop their treatment without any ill effect.

John - So we've been interested in trying to find out if it might be possible to cure HIV infection and one of the big barriers to that has always been that if a patient starts therapy but then stops therapy, the virus comes back. And it's always been assumed that the virus will come back immediately and what we found out in a cohort of patients who are quite unusual was that when the therapy was stopped the virus took a while to come back. And in some cases up to a year for a virus that actually can replicate very rapidly and normally can re-emerge in the body within days of drugs being stopped. So the questions we wanted to ask were how long does it actually take for the virus to come back. Why are these patients different and is it possible that we could predict whether some patients might be in a situation where they could stop therapy for a bit. If you'd like go into a period of remission if you wanted to think of HIV like a cancer. You could have a remission from your HIV so you could come off therapy and have a period of drug freedom if we had to go back on again.

Chris - How did you explore these patients? Do you think they were a very unusual sub-set or do you think that they're representative of the broad population of people who have HIV and we just need to know how to spot people like this in that population.

John - What is interesting about these patients is they're all diagnosed very early. The history of most HIV infection and the majority of patients that we see in clinic is that they're diagnosed often a few years after they are infected. During which time the virus has taken hold, it's spread through the body and it's sort of laid itself down in a number of different places. With these patients, they're all diagnosed and started on treatment within around six months and actually most of them were started on treatment within a few weeks of being infected. Because of that short time involved it looks as though something unusual happened and the virus didn't take hold as well as it might had done otherwise. So when therapy was started, the effect was much greater on sort of the total viral burden if you like. And this meant we think that when therapy was eventually stopped, most of the patients did rebound reasonably quickly but in a few of those patients there was this long delay. And we think it was that very early therapy which is unusual which gave them that advantage and this would then argue for screening for patients early to find out if someone has been infected and get them on therapy very quickly because that might make a difference to their sort of longer term outcomes.

Chris - But obviously to screen for something you've got to know what you're looking for. There's got to be some kind of marker. So do you have any feelings to how you could identify people who fit into that category?

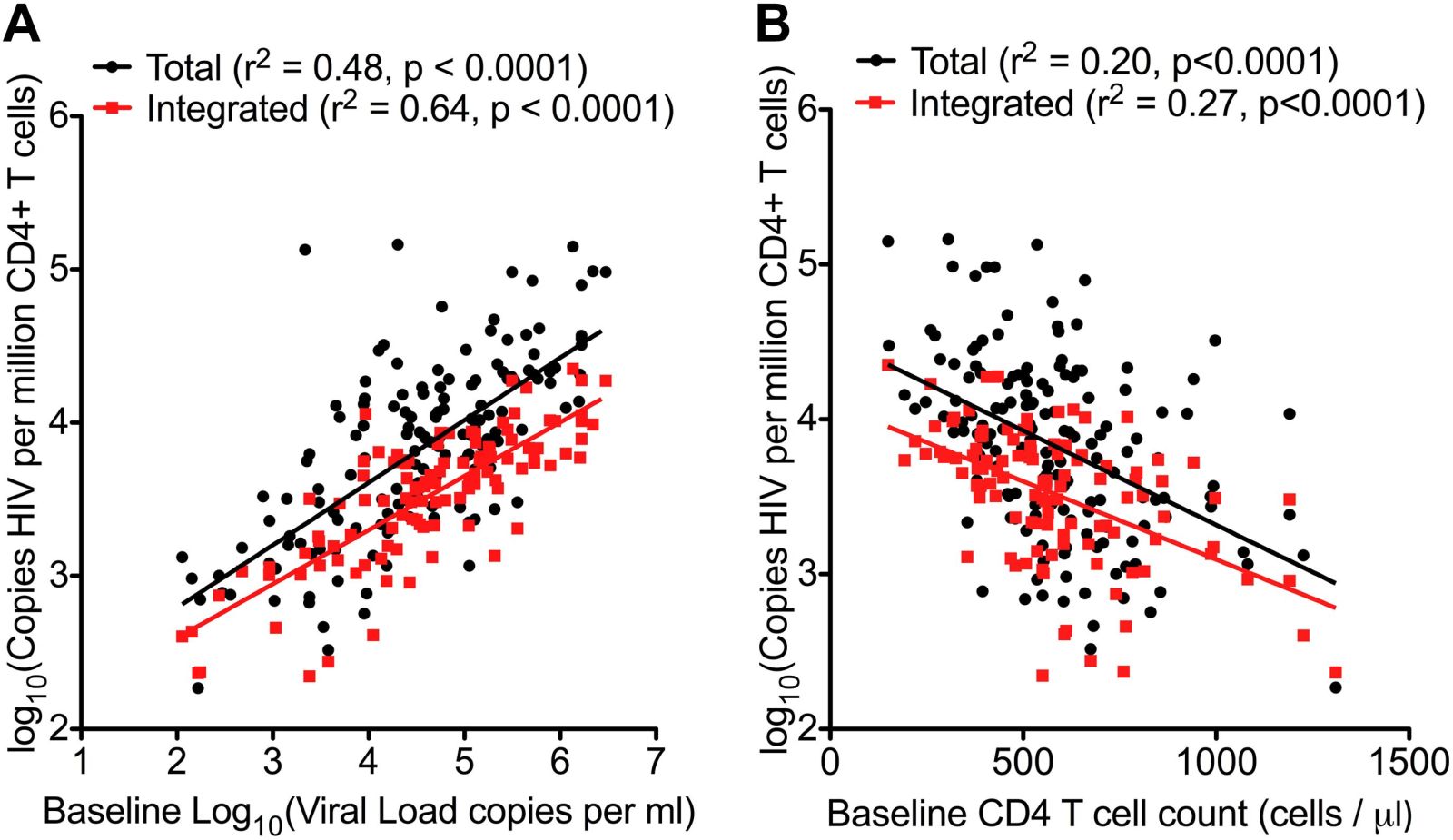

John - Yes. So the first thing is to identify patients with primary infections. Once they've been diagnosed and started on therapy, the question is then - is there another measure we can use to say you might be someone who could have a period of remission. This is not yet within any sort of clinical algorithm or protocol if you like and everyone has to stay on therapy but we're thinking about the future. We're looking for sort of tests or bio-markers, that's another name for them, which can help us predict patients and this work that we've done recently: There was one bio-marker which is a measure of how much viral DNA is hiding within the blood cells and if you actually quantify that with a very sort of very precise assay that marker was a predictor of when the virus came back which was a surprise. We always knew that mark was a predictor of how your disease might progress if you became unwell but we didn't know that it would predict actually whether the virus would wake up or not and that was also the difference that we were able to discover.

Chris - In other words, the interpretation of what you find in the more of that DNA there means that more cells are infected and that person's what?, More likely to have a rapid reinstatement of their virus if you stop treatment?

John - Yes, and what we found was that the patients who had the most cells containing viral DNA were the ones who rebounded most quickly. On the other side of the coin, the patients who had only a little bit of DNA hidden within their cells behaved slightly differently. Now some of them also rebounded quite quickly but a proportion of those ones with low DNA had this very sort of protracted duration of being off therapy without the virus coming back.

Chris - Why do you think they have a low risk of the virus coming back? Do you think that just reflects the fact they don't have very much virus lurking in them in the first place and therefore if there's a chance that it's gonna reactivate if you've got less virus there already, you've got fewer rolls of the dice. So it's less likely to happen and it takes longer before it does.

John - Yeah. It may be something that simple. I mean I think one of the caveats to what we've done is that we have taken blood samples and we've only looked in the white blood cells for DNA using a reasonably simple assay. But what we didn't do, we didn't look in other places where the virus can hide - the lymph node, the gut, bone marrow, even in the brain. And so when the virus comes back it could be coming back from any of those places. Our measures are sort of a marker of what might be going on elsewhere in the body but I think you're right I think essentially it comes down to sort of the burden of disease that you have on board and if you can reduce that down to a very low level then the odds or chance of the virus coming back are statistically less.

- Previous Regulation rules

- Next Missed connections

Comments

Add a comment