|

|---|

A single nerve that runs from the brain to the gut may hold the key to treating a host of the 21st century's biggest public health challenges, according to scientists working to beat obesity and Crohn's disease.

Europe has a weight problem - and it's getting worse. One in three 11-year-olds in the European region is overweight or obese, according to data from the World Health Organization (WHO).

'It's a lifestyle issue,' said Professor Steve Bloom of Imperial College London, UK. 'We sit in front of screens all day, we drive everywhere and food is abundant. The trouble is that this builds up fatty tissue which leads to obesity, diabetes, stroke and cancer.'

The most common remedy for serious cases of obesity is bariatric surgery - procedures that reduce the size of the stomach by applying a gastric band, removing a portion of the stomach or bypassing the stomach altogether.

These operations drastically reduce appetite and the patient loses weight but there is a problem, says Prof. Bloom.

'We cannot perform surgery on the scale that would be required given the growing numbers of overweight and obese people in society. We would not have the resources, the complications from surgery are high and one-off surgical procedures do not allow for adjustment if a patient loses too much or too little weight.'

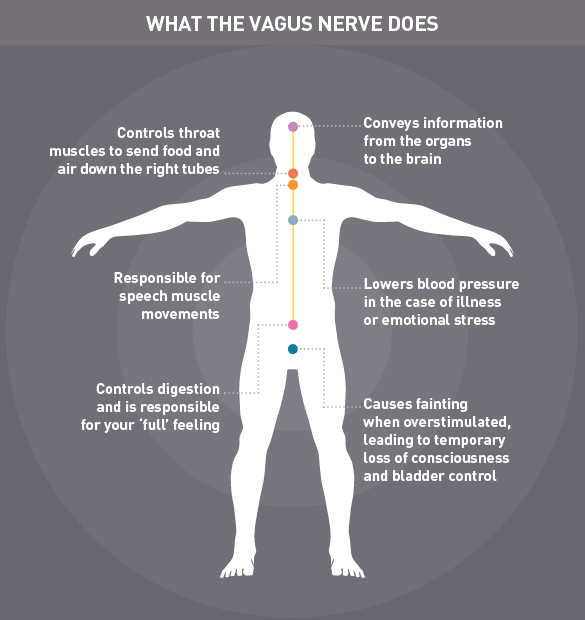

However, by studying the impact of bariatric surgery, scientists have discovered that the procedure affects the vagus nerve - a long nerve that plays an important role in sending messages between the gut and the brain. One of its jobs is to tell the brain when the stomach is full, effectively switching off hunger.

This gave researchers an idea. 'Our mission was to try to find a way to control the vagus nerve without using dangerous surgery, and in a way that could be adjusted according to the needs of the individual,' said Professor Bloom, whose I2Move project is funded by the EU's European Research Council (ERC).

The project has paired Professor Bloom's interest in metabolism with the knowhow of engineers in order to devise a way to turn hunger signals on and off using electrical stimulation.

Professor Chris Toumazou of Imperial College likens the vagus nerve to a microprocessor that sends signals to and from the brain. It has many functions within the human body and Prof. Toumazou has previously studied whether electrical stimulation of the nerve could help to treat epilepsy.

'My frustration with earlier approaches to vagus nerve stimulation was that electrodes can be very unintelligent. They stimulate at regular intervals - say, every five minutes - but do not incorporate patient-specific feedback,' he explained.

Using regular electrical stimulation in epilepsy patients can have downsides including fatigue and headaches. A similarly blunt approach to controlling appetite would fail to react to whether the stomach was full or empty - giving electrical pulses even when it's not necessary.

Responsive

To develop a smarter, more responsive system, Professor Toumazou and colleagues have used sensors that detect chemical changes in the stomach. The team is working on a tiny implantable device that would sit close to the vagus nerve in the gut where it could detect hormonal changes.

'When the hunger hormone is detected, the device blocks the nerve so that this signal is not sent to the brain,' said Professor Toumazou. 'This gives real-time appetite control without the need for major surgery.'

The device is set to enter trials in clinical volunteers as early as this year and, as the path to market is much quicker for new medical devices than it is for medicines, it could be available within five years.

'It has taken a truly interdisciplinary effort to get here as there was a technical mountain to climb,' said Professor Bloom. 'This is (a) step toward a larger challenge of achieving total body control and is applicable to many diseases.'

The more scientists have learned about the vagus nerve, the more valuable it appears. This versatile nerve also has a role in controlling inflammation in the gut. For people with chronic inflammatory conditions such as colitis and Crohn's disease, vagus nerve stimulation could ease symptoms.

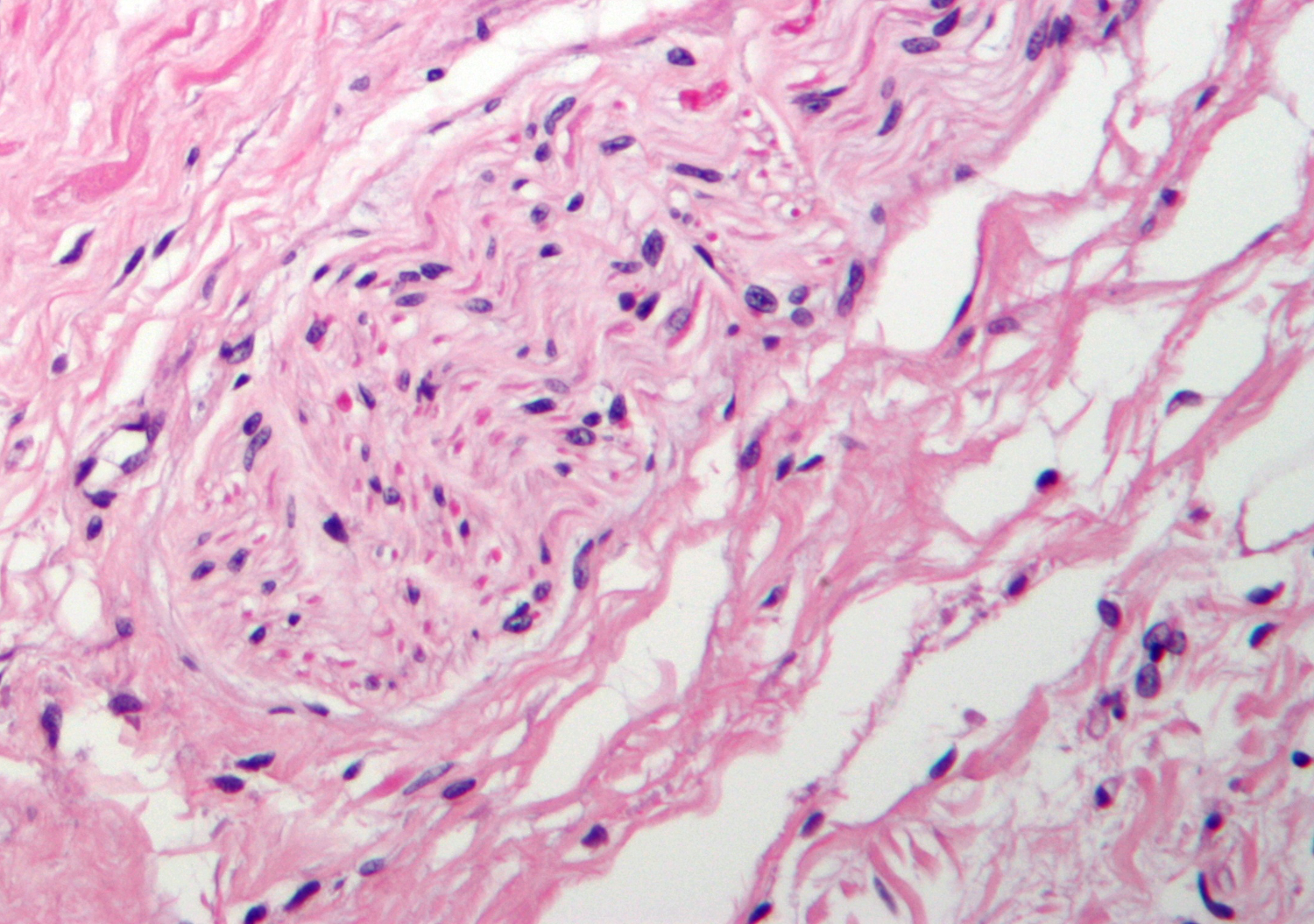

|

|---|

Professor Guy Boeckxstaens, a gastroenterologist at the University Hospital Leuven, Belgium, is heading up the ERC-funded CHOLSTIM project which has been exploring the role of the vagus nerve in the gut.

'We are seeing promising anti-inflammatory actions in animal models for colitis and food allergy,' he said. 'Depending on the outcome of that work we hope to move to a small clinical study of around 10 patients.'

Whereas vagus nerve stimulation through the neck is used in certain types of epilepsy, the goal for treating chronic gut disorders would be to insert a pacemaker into the abdomen. It would remain there for several years, like a cardiac pacemaker implanted to regulate the heartbeat.

Professor Boeckxstaens has been in contact with a medical technology company that designs devices in this area and, once his team establishes the right stimulation parameters for their target patient population, the new device could become available quickly.

'The clinical translation can move very fast once we get the basic science right,' he said.

Other autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, are also in the crosshairs of vagus nerve experts.

'Inflammation is even more important than was imagined 15 years ago and the interaction between the vagus nerve and the gut has therapeutic implications for a whole range of disorders,' Prof. Boeckxstaens said.

'There is a lot of enthusiasm about this topic. Time will tell whether it is justified or not.

Comments

Add a comment